AMIKO LI

Passaggio

Curated by Li Jia

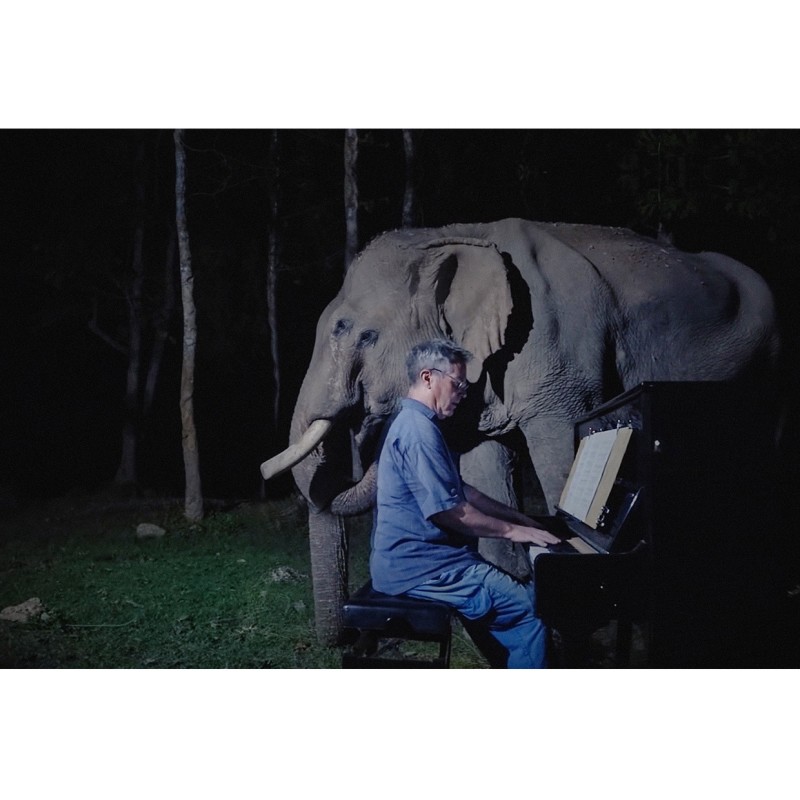

Photography is silent, but does it really have nothing to do with sound? Could there be a passageway that connects listening on one side and looking on the other? Can we hear a picture or see its voice? How should we envision a picture as a sound and a sound that becomes a picture? Amiko Li asks these questions in his project Passaggio. Of course, this is not the first time someone has raised these issues. Near the end of Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes, in his usual disorganized way, tossed out this disjointed, understated pronouncement: “The photography must be silent (there are blustering photographs, and I don’t like them): this is not a question of discretion, but of music.” At least, for Amiko Li, photographs are not silent, and their sound is not limited to music; photographs are more like background sounds diffused throughout our everyday lives. These sounds are lasting, overflowing, mixed, and subtle; they are not easily separated, identified, or remembered, but they are ubiquitous and endless, like a whisper, a rustle, a murmur, or a breath. We are surrounded by, but often unaware of, these sounds; they are innate sounds that connect all living beings.

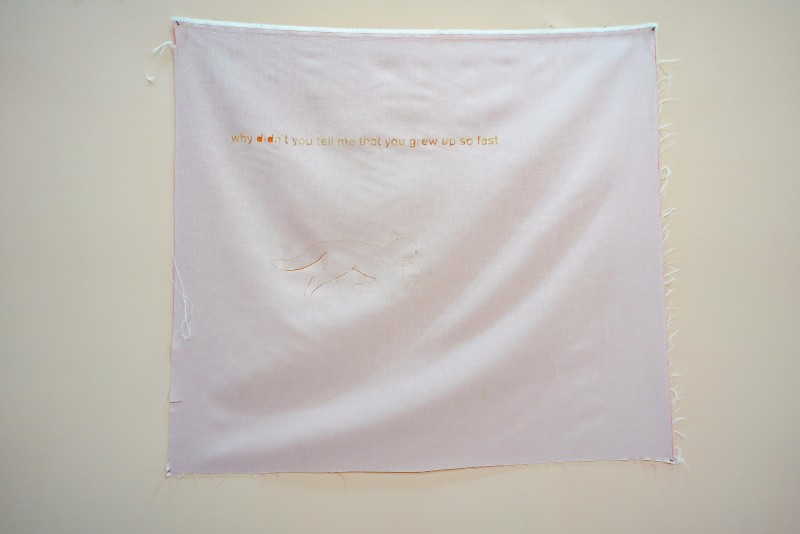

The title of the exhibition, which draws on a term in vocal music, suggests the place of sound in photography. “Passaggio” refers to a transitional area between vocal registers. Like traversing a body of water with submerged reefs, the throat will often get stuck at that transitional point when singing. A smooth and natural transition can only be made after long training. As a result, the term “passaggio” is closely connected to the body. The skill of this transition, which requires the throat and breath, is also related to the body’s development: from childhood to youth, everyone experiences a transition from the head voice to the chest voice. It reminds us that sound is heard, but it also expresses something of inherent experience. This is an ambiguous concept, which matches the rather complex layers of the exhibition. Li does not simply present pictures or the “sounds” of pictures; there is also pure sound, videos with sound, and an intricate viewing experience. Viewers first encounter pictures in a bright, white-box exhibition space. Upon turning a corner, they enter a dim, closed room and are surrounded by videos with sound, all placed at differing heights. In a final, even darker room, the exhibition ends with a monologue by the artist—a video projected over an entire wall to accompany the artist’s voice reading his notes aloud. Visitors must make several transitions: from pictures to sounds to pictures that accompany sounds to sounds that accompany pictures.

However, what is it that produces an essential connection between visible, fixed, and material pictures and fluid, uncatchable, fundamentally immaterial sound? At first glance, the photographs and videos exhibited in “Passaggio” do not share any common category or specific theme. They are not photographs about sound; they are neither records of performances and events, nor do they present objects making sounds or people listening to sounds. They do not seem to have any intention of creating a visual rhythm, through composition or color, that is so often compared to music. These pictures, which are all untitled, seem to simply exist as they are. They include many details of everyday life, and they may even be things that enter into our consciousness in only the slightest of ways: a street scene, furniture, a portrait, a patch of light and shadow, a corner, a part of a courtyard seen through a frosted window, an interrupted trail in the mist, an ordinary door, an ordinary room, a desk, a silhouette, or scattered objects. It might be better to say that the photographs are sound, rather than about sound; they are ubiquitous, endless, and difficult to perceive. Sound is like air; it has run throughout all of human time, never interrupted, even in sleep. In everyday conscious experience, sound is often concealed as background noise. The vast majority of sounds are like the vast majority of times, in that they can only be experienced unconsciously, and cannot be perceived, distinguished, identified, or remembered. “Thus it is in the nature of sound to be often associated with something lost—with something that fails at the same time it is captured, and yet is always there.” Couldn’t this description also be applied to photography? To a certain extent, isn’t photography just as deeply enmeshed in time and focused on capturing something lost in the unconscious?

This may be the true subject of Untitled; it attempts to examine which qualities photography shares with sound. One is time, their shared secret. These photographs also seem to be emitting a sound. If you stand next to them for a few more seconds, you may be able to hear it. For example, in the pictures of that corner of a room faintly illuminated by sunlight or those windows covered with cream-colored curtains, there is still an illusion of sound, even though they are empty, because the air quivers and conveys the distant sounds of the city. A door appears repeatedly in this series; sometimes it is the entire door, and other times it is just a small part of it, or the dappled light dancing on it, filtered through an invisible tree above. This kind of imagery immediately brings to mind another master of listening. In the beginning of In Search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust elaborates how the rustling of a chestnut tree’s leaves became the tree’s borders; their slight trembling, in the most graceful and exquisite way, neither disturbed the rest of the tree nor stopped on the trunk; they always continued to move. In the same way, sound emerges, glides, and envelops us. We cannot instantly capture all of it. Sound does not exist in the pauses; it needs time to express itself. Similarly, these pictures are not at all concerned with creating that decisive, key moment; they seem to simply exist, relaxed and muffled like all living beings.

Amiko Li introduces his own voice, like a footnote, into the second half of the exhibition. Six mini projectors play different sections from the same video. Here, the artist appears in the middle ground, variously in a room, at the front door, and on the nearby lawn, mumbling as he reads from the diary he kept during the pandemic. In this part, photography does not appear, but what is present are the related sounds and voices. The visual and the visible are reduced as much as possible, and the flesh-toned walls of the room create a sense of intimacy and connection to the body. In this passaggio, the sound comes from neither outside nor inside; it is produced where the two meet, and our bodies are the only zone of admixture. Therefore, in the final section of the exhibition, the photographs have been entirely transformed into pure sound. The external distance that seemed to have been eliminated has actually been magnified; it is occupied by the lips reading aloud and the trembling fingers holding the paper, in the light and shadow of sound.

By Li Jia