GUO GUOZHU

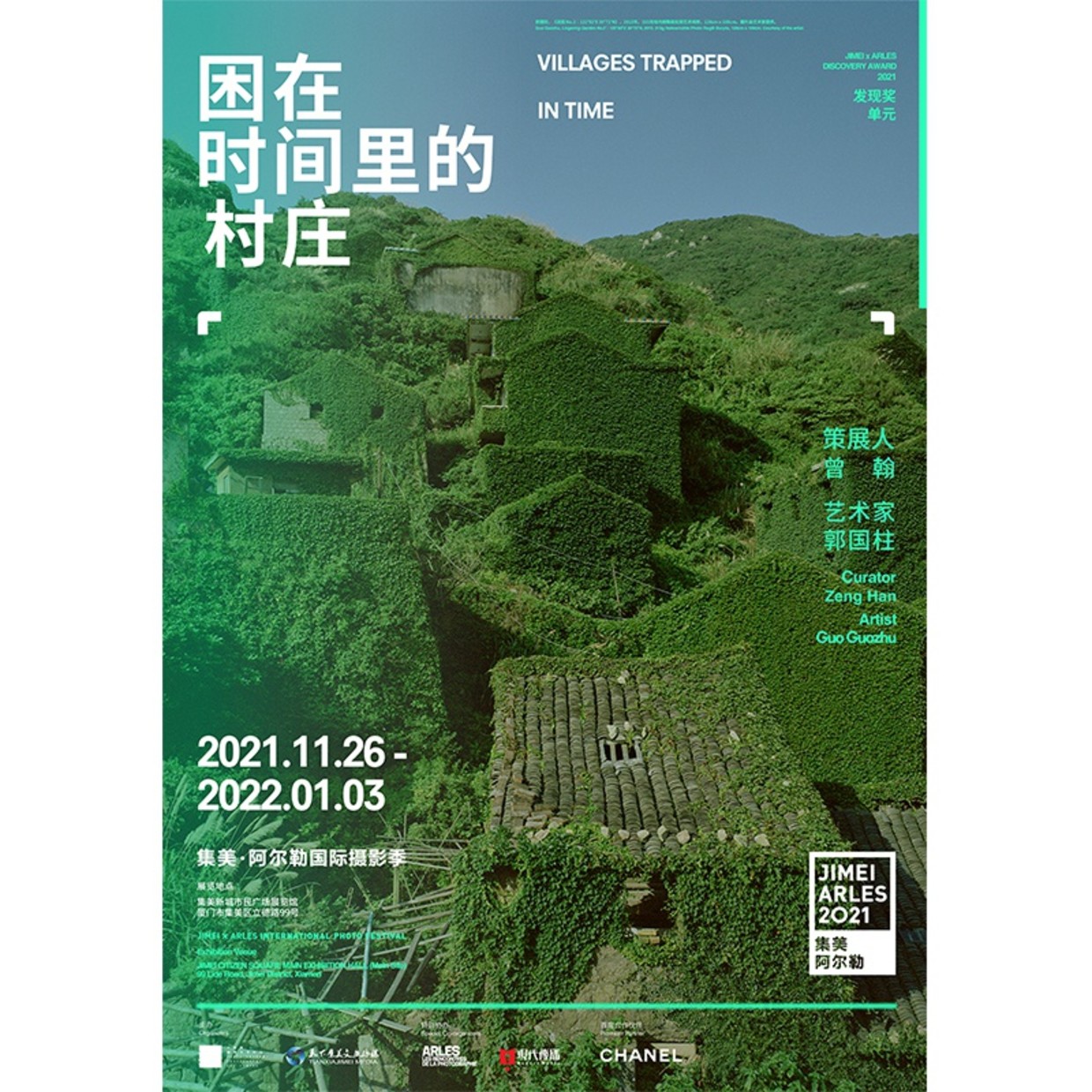

Villages Trapped in Time

Curated by Zeng Han

In a sense, ruins are the representations and symbols of time’s materiality; they encompass two mutually complementary dimensions: the suspended moment and the continuous flow of time. Guo Guozhu has documented the changes in Chinese villages since 2012, and he invariably interweaves these two dimensions in his work. When all of these images of the Chinese countryside are presented together in a closed three-dimensional space, they are trapped in time, as if the viewers were watching that great scene from Interstellar.

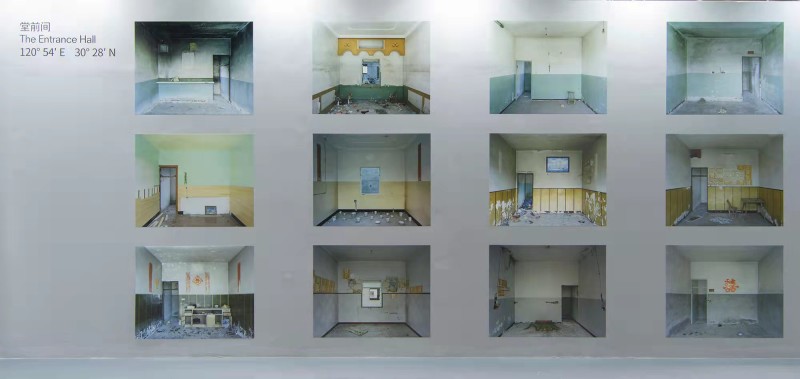

His first project was Xinwan, a video about demolished houses and moments in time. In his Relics of a Village series, he took portraits of the living spaces and objects that villagers had left behind, offering a glimpse of their memories and experiences. In The Entrance Hall, he made a typological study of the kinds of receiving rooms unique to rural areas. The architectural reality of this vanishing cultural practice points to the mental adjustments that need to be made. Finally, in Lingering Garden, Guo photographed empty villages all over China that had been abandoned due to urbanization, sampled in the manner of a large-scale field study. The series progress from the points in time shown in a moment of demolition to the chunks of time manifested in abandoned objects to the surfaces of time shown in living spaces, before finally expanding into the linear time of ruined, empty villages that convey historical narratives. Simultaneously, his projects have progressed from photographing emptiness to objects to interior spaces, before finally expanding into village architecture and the vastness of nature. This layered progression has built a historical panorama of changing time and space in China’s transition from an agrarian to a post-industrial society since the beginning of the twenty-first century.

French historian Pierre Nora wrote, “Memory and history, far from being synonymous, appear now to be in fundamental opposition. Memory is life, borne by living societies founded in its name. […] Memory is a perpetually actual phenomenon, a bond tying us to the eternal present; history is a representation of the past.” Guo Guozhu was born and raised in a rural area, but he later moved to the city to study and work. He has experienced the continuous dislocation and loss of social relationships, lifestyles, and values and the gradual reshaping of the person he wants to be. As someone who experienced urbanization, his photographs of the vanishing Chinese countryside stem from his own need for and anxiety about memory, and he believes that memory’s significance is as the representation of history. Guo fuses personal and social history; he begins with the history of everyday life, and using the tools of microhistory and photography, a medium for the visible history of narrative, he transforms himself from a witness into a historian. His photography practice over the last decade has shown that “technical images absorb the whole of history and form a collective memory going endlessly round in circles.”

Meng Haoran once wrote, “The affairs of men come and go, with the new superseding the old since long ago.” The tradition of nostalgic poetry in China extols the basic laws of history and human existence, but it differs from the Western poets’ lofty commemorative descriptions of ruins. In ancient Chinese poetry, calligraphy, and painting, ruined steles, buildings, and other manmade objects are representations of a dead history, suspended in time. In contrast, trees, flowing water, and other natural things symbolize living memory and the continuity of time. Guo Guozhu’s photographs perpetuate this nostalgic tradition, paying his respects to these disused objects, abandoned houses, and empty villages with a silent gaze. He never fails to capture the wild plant growth, embodying the tension of memory that resists and shakes off the ravages of time. He specifically chose to take his pictures only during the summer, to capture that consistent, steady green; he is attempting to evade the sadness, as if expressing the adage: “Do not become attached to material things and do not pity yourself.” With the New Objectivity-inspired Relics of a Village, the typology-inspired Xinwan and The Entrance Hall, and the New Topographics-inspired Lingering Garden, and the captioning of every image with the coordinates of the location in which it was taken, Guo has also drawn on the Western rationalist tradition. He has left an objective visual document of his times. History is happening around Guo Guozhu, and his photographs do not simply cherish the past; they remember the present.

By Zeng Han