Since 2016, Kanthy Peng has been creating a series of moving images with her father as the central figure. In Friends, Kanthy invited her father and several colleagues to awkwardly reenact the opening sequence of the eponymous American TV show. Corresponding to this, two sets of shaped acrylic wall paintings titled View from the Window at Le Gras trace the covers of multinational foreign language textbooks that her father had studied over the years. The figures on these covers, with their quintessential American smiles, construct an illusion of an idealized white, middle-class life. Running in Olympics, filmed ten years after the Beijing Olympics, captures Kanthy's father jogging in the Olympic Forest Park at dusk. His pace shifts fast and slow to allow his daughter to keep up, yet his determination remains as unwavering as the mythical Kua Fu chasing the sun. The latest video piece, Ajar, filmed in the harsh winter of 2023, features her now-retired father living in a temple, where he rings the bell, chants sutras, and manages thousands of keys day after day. His repetitive labor becomes a daily rhythm through Kanthy's lens, and while the subtle intimacy between them is carefully restrained, the artist also, at times, intentionally distances herself from it.

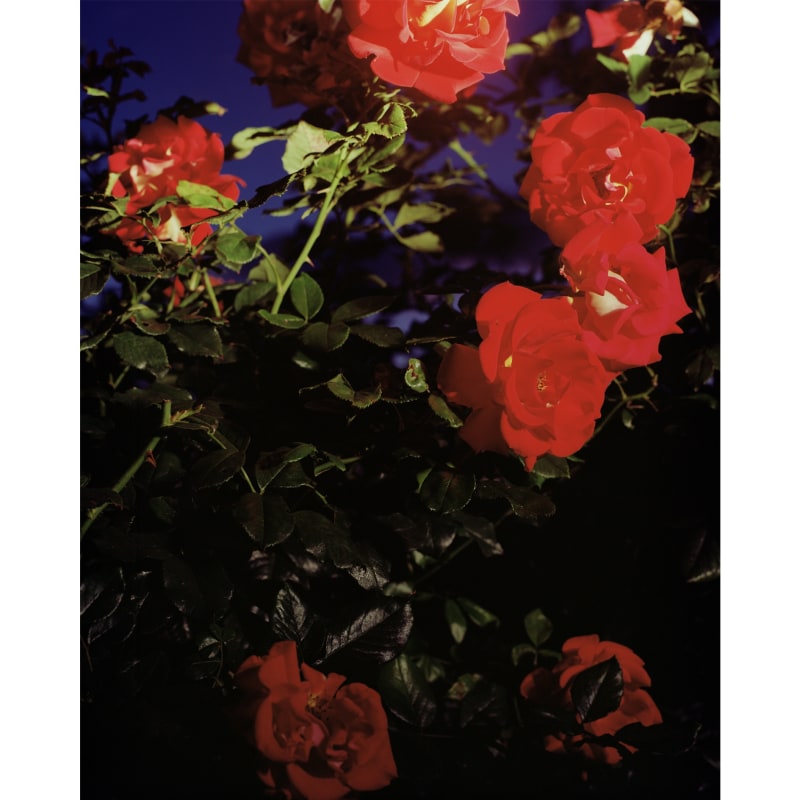

The second thread of the exhibition revisits Kanthy's own experience of being immobilized by depression through a series of photographs. She likens her depressed body to a device receiving signals from the future. These eerily calm images often suggest impending upheaval and destruction. Whether it's legs yearning to break free from the shroud of night or a ladder whose summit remains unseen and unscalable, both point towards a sense of futility. Through these deeply personal works, Kanthy connects individual experiences with a broader societal context, creating a new language that is both tender and intimate, yet sharply poignant. In the exhibition space, these photos intertwine with, reflect upon, and confront her father's videos. The still photographs question the moving images: Where does the faith in running come from? And where does it lead?

A photograph titled Angelus Novus (New Angel) opens another thread linking history, the present, and the future: an innocent Asian tourist stands in front of the sculpture Unconditional Surrender, making a "V" with both of her hands and preparing to take a commemorative photo. It seems like a self-mocking commentary on the artist's sense of displacement, yet the posture and gaze of the tourist coincide with Paul Klee's 1920 print Angelus Novus. In Walter Benjamin's interpretation, the Angelus Novussees that so-called progressions are merely steps toward another destruction, and humanity's visions, hopes, and expectations for the future will ultimately be swept away by an unforeseen storm. When we look again at the recurring image of the "father" throughout the exhibition, his advancing figure eventually fades into nothingness, transforming into the new angel in the flattened timeline. This pattern is echoed in the titles of the last three works in the exhibition: Last Year Flowers Bloomed; This Year Flowers Bloomed; What About Next Year?